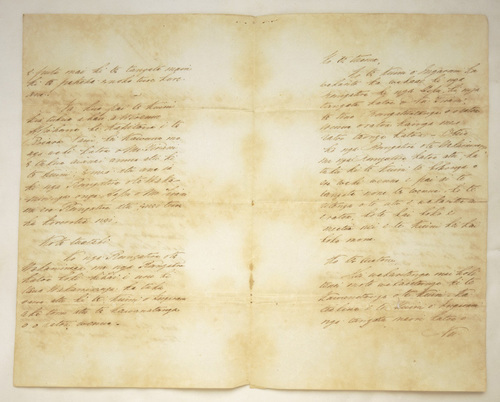

The Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 and was a key turning point in New Zealand history. The signatories were the Maori chiefs and representatives of the United Kingdom. New Zealand was then officially part of the British Empire and Maori people were given the same legal rights as British people. However, this was not a straightforward, peaceful agreement.

There were a number of disagreements over the wording and translation of the Treaty, which led to many disputes between the Maori and the British. Settlers wanted to obtain some of the Maori lands and as a result, the New Zealand Wars broke out in 1843. This did not deter settlers from Britain, who arrived in droves throughout the 19th century and during the early part of the 20th century.

The treaty led to the eventual impoverishment of the Maori people. The settlement of the British and other Europeans brought new infectious diseases to the country which had a devastating effect. The British also brought with them a new legal and economic system. As a result, most of the Maori lands based into European hands and the Maori were left with very little.